Lately I have found myself completely unable to write; like I have all these words, thoughts, and ideas swirling in my mind that, when I sit down to write, will not translate onto the page.

I don’t know when this sudden ‘choking’ of my thoughts began or what causes it. I want to keep this blog current and make progress on my book & article projects, but I’m stuck. As someone who has spent their life writing, not being able to put the article or essay I have been narrating in my head onto paper the way that I would like has been maddeningly frustrating. Even these words don’t seem to be coming out right.

“Just write!” I tell myself. But it isn’t so simple.

Most of my writing is written with the expectation of an audience, be it those who read this blog or my academic peers. I enjoy that fact. I like putting my thoughts and theories out into the world for people to find, read, and think about. …. Except as of late, with this new unwelcome constant where I find myself not able to say anything at all.

What would happen, I thought, if I sat at my computer and simply began telling this story of why I have been so absent from this and my other online endeavors? So that’s I’m doing; breaking from the theme of this blog to say that I have been in creative pit and hope to eventually find the muse that will carry me out of it. I’m still here.

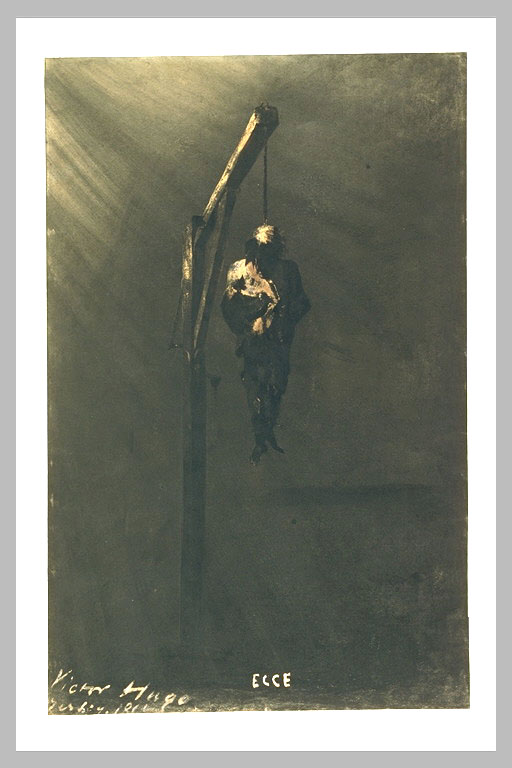

Victor Hugo, The Hanged Man (c. 1855-60). Brush and ink with wash over paper, 12 x 7 11/16 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Throughout my creative drought, I have been contemplating how easily art speaks. All art says something and all art elicits a response. Sometimes, an image will become embedded in our minds and we have to return to it, over and over again, until we are satisfied that we have arrived at what we believe it is saying to us. Bernini had a similar experience when, after seeing Poussin’s Sacraments in 1665, he said “I can’t get the thought of those paintings of his out of my mind.”1

One of the works that has been stuck in my mind is Victor Hugo’s The Hanged Man (c. 1855-60) held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. There is something solemn, even sacred, about this image to me, and I find it remarkable that such a simple composition created by a few strokes of the brush can convey such a profound sense of sorrow, hopelessness, loneliness, and loss. The only mourners that this man has in death are the birds flocking around his corpse.

I tried to resist the temptation to conduct a study of this image in order to bask in the mystery, but the historian in me had to know: Why was this man hung? Surely such a powerful image would not arise without a profound motivation; a catalyst from Hugo’s own life. Indeed, this is one of four drawings Hugo made depicting the horror of the gallows after witnessing an execution in the Channel Islands in 1854.2

Victor Hugo, Ecce, The Hanged Man (John Brown). Black ink and brown wash with white heightening. Département des Arts Graphiques, Louvre, Paris.

Five years later in 1859, Hugo urgently and passionately petitioned to save the life of John Brown, an American abolitionist sentenced to death.3 After false hope that Brown might be released, the abolitionist was hanged. Hugo mourned Brown’s death through the written word and art, creating a drawing which he titled Ecce — Behold. Ecce is a commanding image wherein the viewer is confronted with the injustice of Brown’s execution. A kind of divine light illuminates Brown, who otherwise hangs amidst still darkness, alone. He is a martyr.

Ecce challenged contemporary viewers to reconcile Brown’s horrific punishment with the righteousness of his cause. Those who knew Brown’s story would quickly realize that such a feat is impossible, for the punishment does not fit the crime. Hugo had Ecce distributed through prints, with proceeds from the sales going to various charities, “including those to provide medical supplies to soldiers in the Civil War.”4

Hugo’s drawings were in part the catalyst that led me to thinking about the power of art and the ability of art to speak regardless of one’s knowledge of its context. This has given me the idea to try something new with this blog, a brief series called The Painting Speaks. The Painting Speaks will be an experimental exercise in intentional slow looking and description that relies solely on the work of art itself – a kind of formal analysis. I am not sure when I will be posting this series, but hopefully I will find the words soon.

Notes

1 For the Bernini quote and further reading regarding the idea of images being stuck in one’s mind, see T. J. Clark The Sight of Death (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006).

2 See “Recent Acquisitions: A Selection: 2002-2003,” in The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin (Fall 2003): 36.

3 Florian Rodari, “Shadows of the Hand: The Drawings of Victor Hugo.” Last accessed September 24, 2015. See also “Victor Hugo and John Brown,” The New York Times, April 19, 1902.

4 Matthew Josephson, Victor Hugo: A Realistic Biography of the Great Romantic (New York: Jorge Pinto Books Inc., 2006, originally published in 1942), 432-433.